AURORA—Spontaneous applause doesn’t happen much when films end in theaters, but that was how the audience of “The Original Image of Divine Mercy” reacted March 30 at Rosary High School here.

“I thought it was awesome,” said Kathy Longmeier of Holy Cross Parish in Batavia. “It was beautiful, inspiring. I learned many things I didn’t know.”

She brought her twin 11-year-old sons, Evan and Aiden to see the director’s cut of the film on the first of two nights of screenings in Aurora.

Evan said, “It was pretty good.” He especially liked “the story of how they made the image.”

Aiden agreed with his mom’s assessment. “It was awesome,” he said.

“Awesome,” in fact, was among the most commonly used words audience members used to describe the film.

Paul and Doris Braddock of St. Patrick Parish in St. Charles attended the director’s cut screening.

“It’s the background, and just the information of how it came into existence,” Paul said, “that (makes it) very important to me.”

Doris, who converted to Catholicism in 1984, said, “It totally makes me understand it more.”

The Braddocks were among audience members who admitted the Feast of Divine Mercy isn’t something they feel especially familiar with.

“I’m sure they had it before I recognized it,” Paul said

The feast day is relatively new, though. St. Pope John Paul II declared it at the opening of the millennial Jubilee Year, the same day he canonized St. Faustina, the Polish nun who kept the diaries on which the devotion is based.

For many years she took notes about her apparitions of Jesus, who told her not only to write down what He said to her, but also to have an image of Him created.

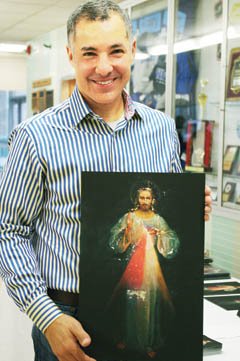

And it’s the story of that image that the film, written and directed by Daniel

diSilva of San Diego, Calif., is about.

DiSilva was at the March 30 showing in Aurora. It was one of more than 70 scheduled in the week before Divine Mercy Sunday, which was April 3. “And that doesn’t count the ones on Sunday,” he said.

Before the show, he was busy in the entry hall of Rosary High School, setting up samples of images of the Divine Mercy at various stages of restoration. Money raised from the sale of the images, he said, will help build a pilgrim’s center in Vilnius, Lithuania, where the original image is displayed in a small chapel.

Across the hall, others were setting up tables of portraits of people whom diSilva interviewed for the film. While each person is recognizable in the paintings, he said, showing them is a way to remind audiences that no painted image can capture the whole essence of the person being painted. How much less, then, can we capture the essence of Jesus in a painting.

Yet that was what St. Faustina, and her spiritual director, Blessed Michał Sopoćko, a priest and professor at Vilnius University, tried to do when they commissioned Lithuanian portraitist Eugene Kazimirowski to make the painting of Divine Mercy in the 1930s.

From its completion, the painting has undergone its own adventures.

“The troubles are the plot,” di Silva says of his documentary.

He came to film making after spending a career as a musician, playing mostly smooth jazz , Latin and Afro-Cuban music.

“I had a conversion about 11 years ago,” he said. That led, in part, to his forming a Catholic Christian band, Crispin, named for the saint who was a preacher by day and cobbler by night.

On the last day of a tour with the band, he met a man in Vilnius who insisted di Silva come with him to “see something.” It was the original image, hanging in a small chapel. He was allowed to spend the night in the shrine.

There, he said, he began to realize he had to tell “the story about an image that was lost, abandoned, stolen, kidnapped.”

The road to production wasn’t easy, but they were well underway when Pope Francis announced the Jubilee Year of Mercy being celebrated now. He is thrilled that it was ready for its premier in Vilnius on Feb. 22, the anniversary of St. Faustina’s first visitation by Christ.